[Left] Portrait of Anouska Ingerdahl Kobus; [Center] Portrait of Julie Koldby, courtesy of the artist; [Right] Portrait of Astrid Kajsa Nylander, courtesy of the artist.

[Left] Portrait of Anouska Ingerdahl Kobus; [Center] Portrait of Julie Koldby, courtesy of the artist; [Right] Portrait of Astrid Kajsa Nylander, courtesy of the artist.

Julie: We are sitting in the back room of OTP on Vester Farimagsgade 6.

Astrid: In our exhibition called minijobs & to-dos, which opened yesterday – Friday the 23rd of May.

Anouska: It was a good night. It was cold and raining, but fun and a lot of people came. We're going to have a conversation about the exhibition, your practices and how they link and open up potentials for new explorations of your works. But we are also going to talk about the themes that you both work with. Could you tell us about how you felt being invited with the other artist? Astrid, did you know Julie's practice before?

Astrid: I didn't know Julie's practice before – I had seen a few images online. First you only see the images without knowing much more, but I could relate to the way the works had been produced in terms of the surface treatment. It seemed like a good contrast and I saw connections to my work. Recently I have been interested in exploring how layers of paint and traces become some kind of record. I've been looking at facades of buildings. They have one colour, and then someone is tagging on it then that is being erased and painted over with another layer of paint, but in a slightly different colour. The patches become a record of time passing. That's something I could recognise in your work. There's an interest in allowing layers to be visible.

Astrid Kajsa Nylander & Julie Koldby, minijobs & to-dos, installation view, 2025. Courtesy of the artists and OTP Copenhagen.

Astrid Kajsa Nylander & Julie Koldby, minijobs & to-dos, installation view, 2025. Courtesy of the artists and OTP Copenhagen.

Anouska: Probably the formal aspect distinguishes the two of you most, I would say. Astrid, in your paintings, you also have layers and forms of depth and perspective, obviously, but evident in a different way than in Julie’s works.

Julie: It just makes me think of Katharina Grosse - when you talked about this temporary way of working. I’m just really into her at the moment in terms of her big outdoor paintings on landscapes or buildings or taking over that space. Do you resonate with her?

Astrid: I know her work and I think it's very spectacular. It's impressive. It's hard not to be impacted by it because it's an immersive type of painting. It is a textbook example of what “painting in the extended field” could be. Her painting is involving architecture, not pretending that the architecture is something neutral in the background. She's highlighting the space, and that's something I'm interested in, in my work. The minijobs that I'm showing here, is a series that I've been working on for almost 10 years. The minijobs are highlighting the actual space that they're shown in, pointing at the fact that this is a surface that something is connected to. It's not only happening within the frame of the canvas. The canvas is an object, which is a surface.

Anouska: Connected to something.

Astrid: Exactly. And it is connected to the other works that are there. Now they are connected to your works, Julie. So, I can relate to Grosse’s perspective. Even though I must say, I don't know too much about her own thoughts on her work. But it's very direct.

Astrid Kajsa Nylander & Julie Koldby, minijobs & to-dos, installation view, 2025. Courtesy of the artists and OTP Copenhagen.

Astrid Kajsa Nylander & Julie Koldby, minijobs & to-dos, installation view, 2025. Courtesy of the artists and OTP Copenhagen.

Julie: Yes, it's very direct. Her way of working with in situ painting on top of something and responding to architecture. I feel like you do the same, in a way, on a small scale. Even though you do work within the canvas, to me your minijobs open the architecture in the space. And there's something about scale. That wall where it's hanging on could be suddenly so small, or the wall and painting could only be standing by the thread tying them together.

Anouska: The scale accentuates the other space around it. Katharina Grosse is quite brave in her use of colour and that she takes up so much space. It's hard not to be impacted. But it's still brave of her to transgress aesthetic categories that we normally deem to be something that's kitsch or ugly.

How do you find that people tend to relate to your works? Do they resonate with people or is it difficult to have people understand what you're trying to express?

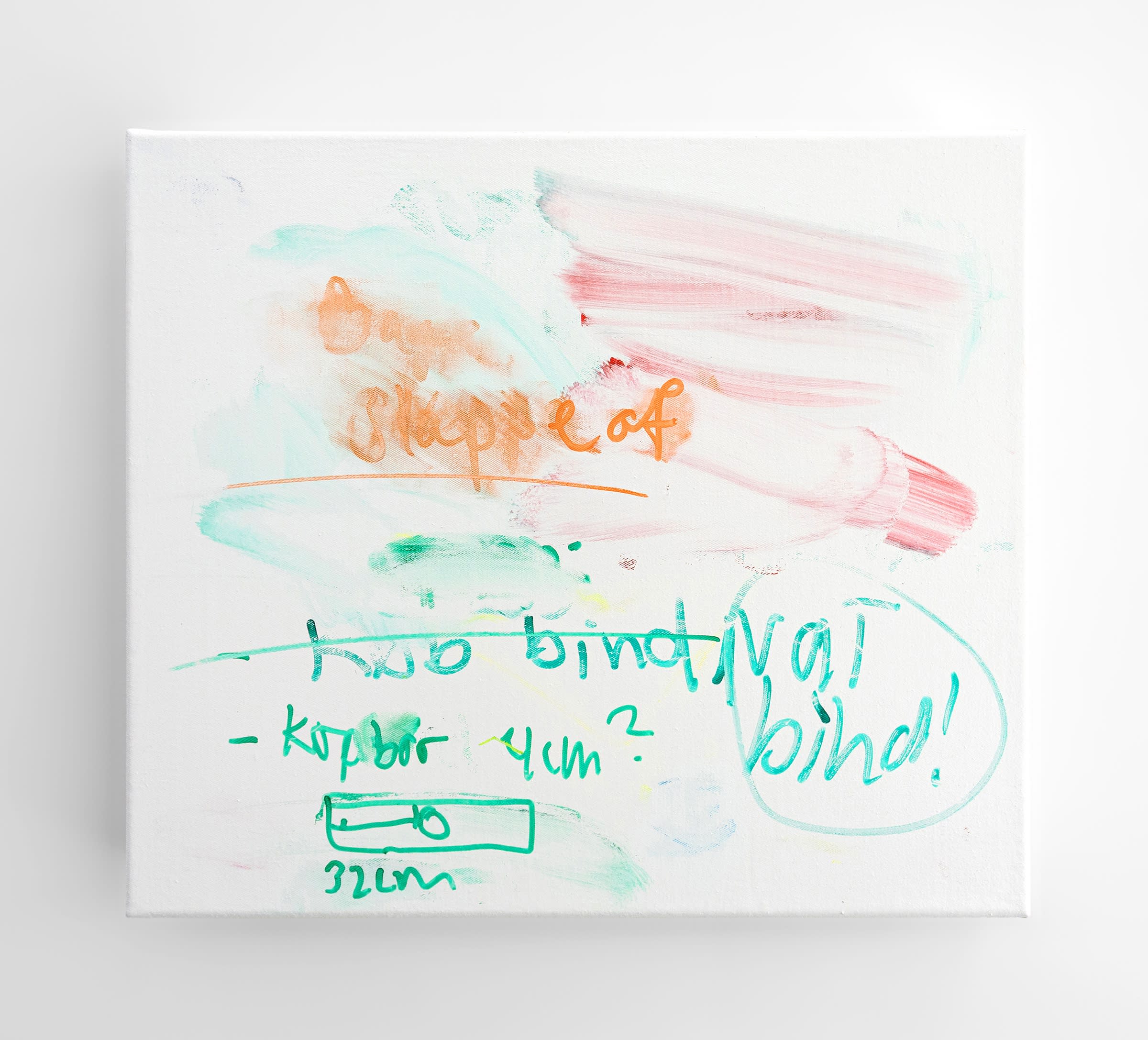

Julie: It's a good question. This is the first time I'm showing these works. I've been working on them for 2 years – these ongoing to-do list surfaces that I'm reusing every day. They are stretched canvases. And then I prime the canvas with an industrial whiteboard paint. So the surface of the canvas gets this glossy whiteboard look. And then I write on top of them with the whiteboard markers. So they are really functional. And then I write my to-do lists for the day.

It could be “buying pads” or an application deadline or just personal everyday to-do's mixed up with work to-do’s. I don't think about “buying pads” as something that is personal when I'm writing that on my to-do list, but suddenly when it's in this space, of course I'm aware of it, and it situates itself into another discourse. It has a more political or female-gazed perspective. There was a woman here last night who said: “I really feel seen by your work.” And that was really nice to hear.

Julie Koldby, To-do painting 5 (Natbind!), 2025, whiteboard paint and whiteboard markers on canvas, 35 x 40 cm / 13.8 x 15.8 inches. courtesy of the artist, and OTP Copenhagen.

Julie Koldby, To-do painting 5 (Natbind!), 2025, whiteboard paint and whiteboard markers on canvas, 35 x 40 cm / 13.8 x 15.8 inches. courtesy of the artist, and OTP Copenhagen.

Anouska: I think that functional part of it is interesting and the way you break with that function, because the works are also wild. You write in an intuitive stream-of-consciousness way. The motif in Astrid’s works is also functional – it is a button with buttonholes – but conveyed in a completely different way. Astrid could you elaborate on working with the minijobs series?

Astrid: I have memories from my childhood when I was at my grandmother's house. She has always been sewing and weaving and working with textiles. She has a collection of buttons sorted in colours. So there were many yellow ones, and they all look different. I used to be fascinated with them and then I started drawing buttons. One time I was in an artist supplies shop and I saw ready-made shaped canvasses. I had been working on my drawings for quite a while and it was as if the drawing of the button landed on the surface. I was thinking, “Wow, I could actually paint a round object on a round canvas.” A moment of, “Ah, this is how it should be.”

The shaped canvasses in the artist supplies shop are forbidden in a way, because they are directed towards a hobby artist’s practice. This interested me and was something I wanted to explore. Such things are personal. I easily feel embarrassed and that is something that I want to explore in painting - going to places where I know that I feel uncomfortable. The way I paint is sincere, it is similar to makeup. It is very soft.

Julie: There is a sensitivity.

Astrid: There are emotions connected to it which can seem a bit too cosy, which I want to explore because they have been important throughout my life. It is like when you discover makeup and have this fantasy that you can transform yourself.

Astrid Kajsa Nylander, brick red minijob #2, 2025, oil on linen mounted on panel, 20 x 20 cm / 7.9 x 7.9 inches. courtesy of the artist and OTP Copenhagen.

Astrid Kajsa Nylander, brick red minijob #2, 2025, oil on linen mounted on panel, 20 x 20 cm / 7.9 x 7.9 inches. courtesy of the artist and OTP Copenhagen.

Anouska: For me, there is a lot of tension in your paintings. There is the motif of a thread that is holding down the button, creating the illusion of it being fastened to the wall. It is clear that you are exploring something that creates tension within you. You mentioned makeup and discovering how you are perceived as a woman. You mentioned the aesthetic category of the hobby artist and perhaps these works are about breaking the boundaries of what is perceived as art. The exhibition text is mentioning labour and productivity and last night we talked about how the works convey a certain feminism. There is a sense of breaking free of restraining categories which is evident in both of your works.

Astrid: Art is so much about taste - and that is something undefined and subjective, at the same time, there are unwritten rules or agreements about what is good taste and what is bad taste. Within painting, at least in modern history, it has been an interest for painters and artists in general to push the boundaries of taste and what is accepted. I think it is inherent to an art practice to discover norms. In the minijobs you find an interest in formal painting from the 60s and 70s by Frank Stella and the Danish artist Poul Gernes. I appreciate the work – it’s loud and bombastic. It interests me to go into that type of expression and tweak it. A formal thing like a circle becomes a button. There is a Poul Gernes piece in the SMK collection that resembles a makeup palette. It might not be his intention but it is my association.

Julie: I have been thinking about this heavy history of painting that mainly has been dominated by male painters. It is intriguing to tap into the stage of heavy history and twist it or try to reset the painting, well aware of your references and your interests, but to imagine new potentials. Now I’m also a painter, but it doesn’t matter, I could be on any stage and every stage.

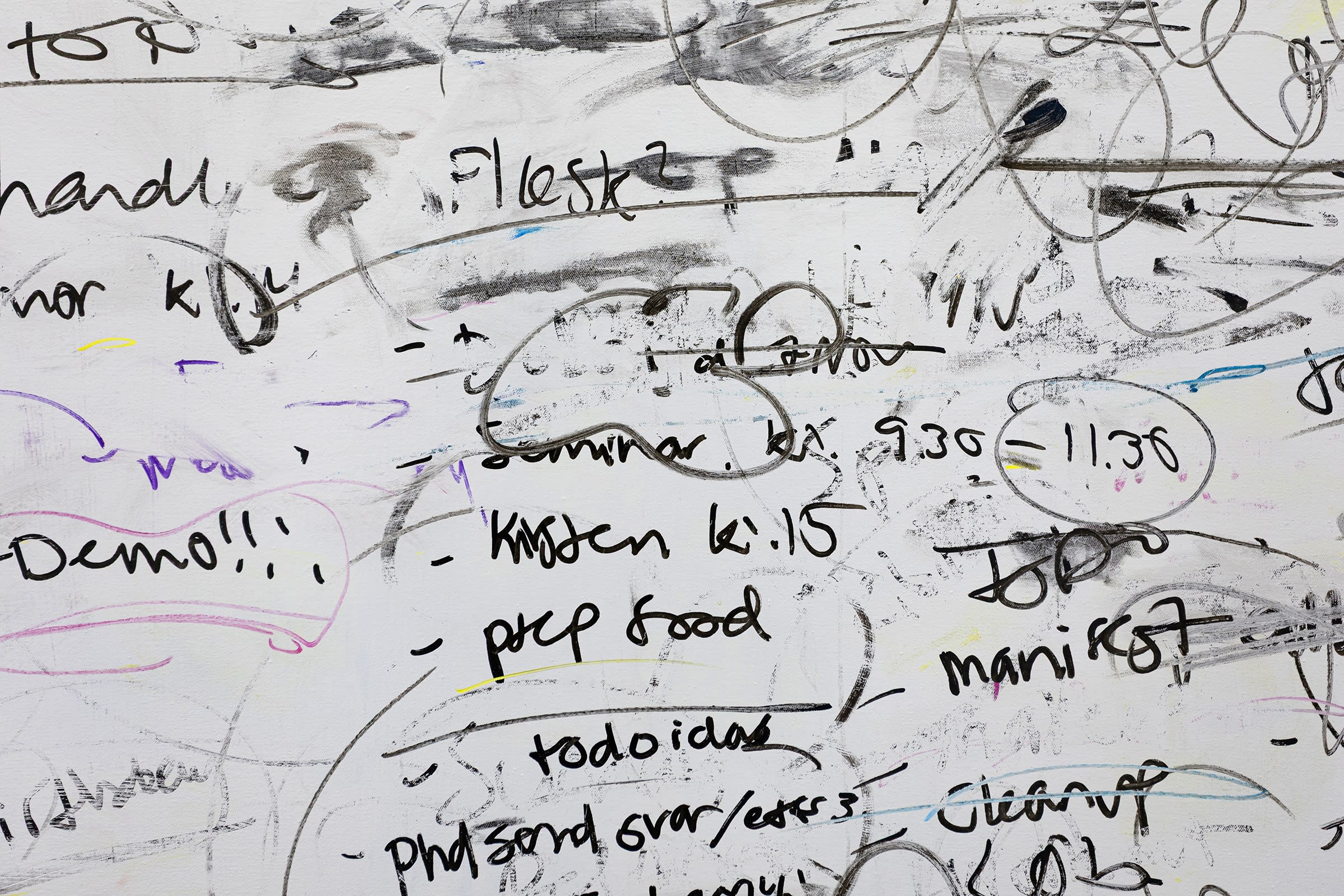

Julie Koldby, To-do painting 1 (Assessments all week), 2025 [detail], whiteboard paint and whiteboard markers on canvas, 160 x 200 cm / 63 x 78.7 inches. courtesy of the artist and OTP Copenhagen.

Julie Koldby, To-do painting 1 (Assessments all week), 2025 [detail], whiteboard paint and whiteboard markers on canvas, 160 x 200 cm / 63 x 78.7 inches. courtesy of the artist and OTP Copenhagen.

Astrid: I’m thinking about the way you use language. You use the canvas to write down things in letters and to make memos for yourself, but when these letters end up on the canvas they become something else that is not words anymore - they become figures, colour and form.

Anouska: They become potentials for something different – a bodily emotion. Your other bodies of work Julie are more sculptural. They play with 3D-rendered material. There are also more performative ways of relating to your work. You create epiphanies of performance. Astrid mentions that she has been inspired by painterly traditions from the 60s and 70s. Correct me if I am wrong Julie, but the artistic movement that I connect mostly to language in your work is Dadaism. Those artists explored what language is supposed to do and what it can do. Do you want to comment on that?

Julie: I think that’s right. They were questioning a system and questioning a way of understanding or imagining something, or a way of sensing the world. In general I am very interested in trying to understand systems and how they are making meanings and how we can break or collapse meanings. A to-do list is a very simple way of trying to organise meaning in your life or manage your life. I think in these works I was interested in doing something as real as possible that is connected to life – the uncontrollability of life and my disagreement and struggle with set structures on physiological or societal levels.

Astrid Kajsa Nylander & Julie Koldby, minijobs & to-dos, installation view, 2025. Courtesy of the artists and OTP Copenhagen.

Astrid Kajsa Nylander & Julie Koldby, minijobs & to-dos, installation view, 2025. Courtesy of the artists and OTP Copenhagen.

Astrid: What you say about the collapse is really interesting. I think both of our works are about that. The collapse is both about structure and destructuring. With the minijobs you can’t tell whether they are being attached or being pulled out – the direction is not clear. It’s similar with the to-do paintings: they are structuring something but they are also being wiped out. The gallery is a small space and it quickly gets full with only a few people. When people walked past the works yesterday night I was afraid that they might wipe them out! I can see the reference to Cy Twombly. Do you know about the attack on one of his works? A woman kissed one of his paintings and left a lipstick mark.

Julie: No I didn't know that - what a power move.

Astrid: His work also has this energy, that you want to be a part of it, because it feels like the process is still open.

Julie: There is an absurdity in my works because I do wipe out the painting almost every day. Whenever I'm done with the to-do list it's over and then there is nothing. But there is still something. Where the process gets interesting for me is where the function of the words suddenly slides into just a construction of colours and form.

Astrid: The collapse is in the process.

Astrid Kajsa Nylander & Julie Koldby, minijobs & to-dos, installation view, 2025. Courtesy of the artists and OTP Copenhagen.

Astrid Kajsa Nylander & Julie Koldby, minijobs & to-dos, installation view, 2025. Courtesy of the artists and OTP Copenhagen.

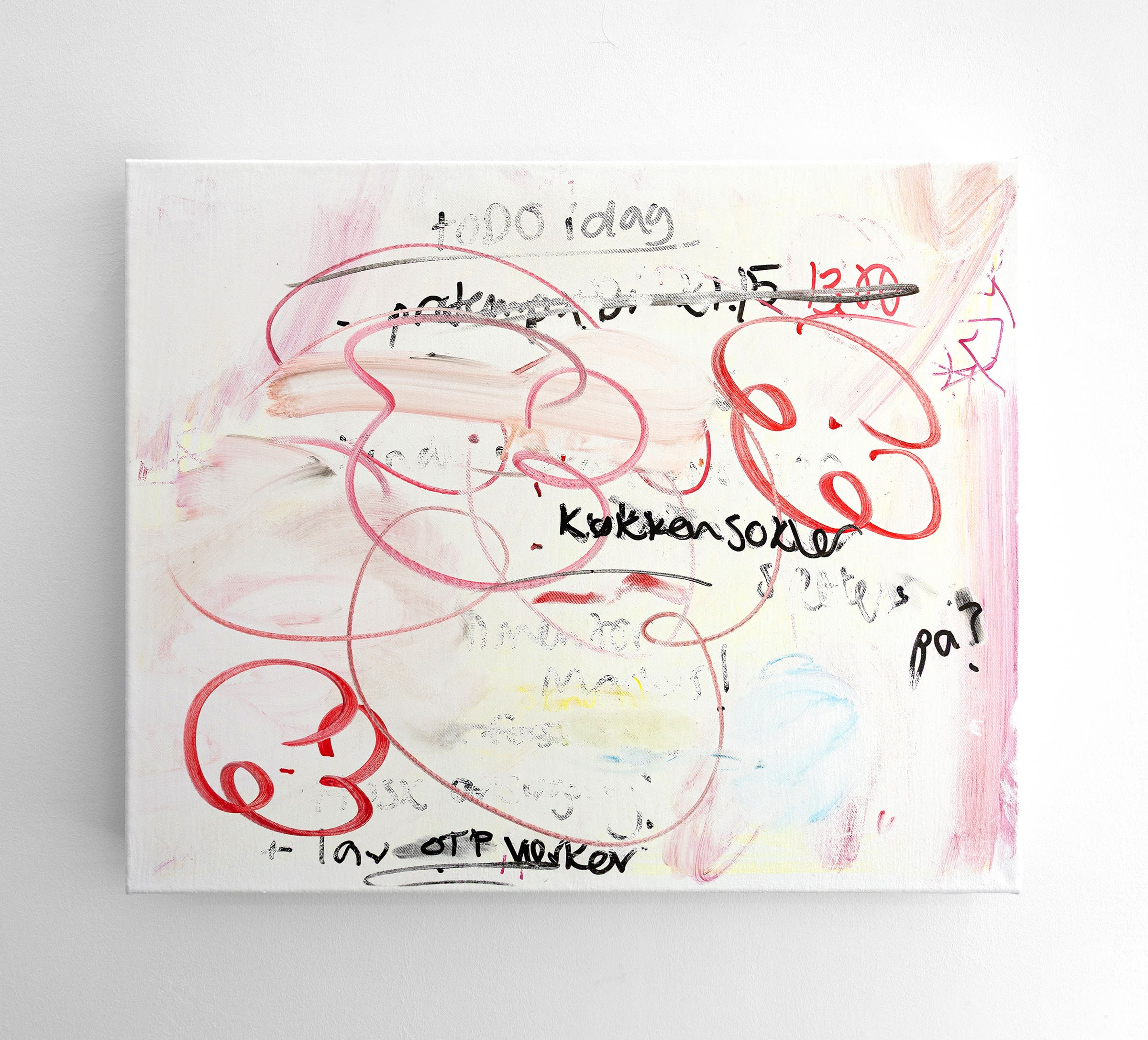

Anouska: Part of what you are researching is when to stop productivity and have a rest or not do anything. There is a limitlessness that the whiteboard paintings convey: “When do we stop working?” or “when do we stop producing?” This limitlessness is also present in your works Astrid – we don’t know where the threads or the holes in the button end. We all deal with this in our economy, we don’t know when it ends and when we can rest. We are constantly moving.

In Scandinavia we talk a lot about free time and how we create a working life that's viable and sustainable and matches the needs of a family – our children or our parents. Our way of working is changing because we want this free time, and we want to be able to travel and explore ourselves and each other. At the same time, we are caught in a system of constantly producing something. I don't know how it was living 100 years ago. I am probably being nostalgic but I don’t think there was this constant scrutinising, producing or optimising of your inner self.

Julie: Especially in the realm of accelerationism – high speed social change, technology and just the pace of life. On a low-key level being able to work as an artist I have two full-time jobs. For a long time, I was trying to separate my artistic work and corporate work life, but I realised it’s all intertwined.

Anouska: That’s present in your to-do lists.

Julie Koldby, To-do painting 6 (Køkkensokler på?), 2025, Whiteboard paint and whiteboard markers on canvas, 45 x 55 cm / 17.7 x 21.7 inches. courtesy of the artist and OTP Copenhagen.

Julie Koldby, To-do painting 6 (Køkkensokler på?), 2025, Whiteboard paint and whiteboard markers on canvas, 45 x 55 cm / 17.7 x 21.7 inches. courtesy of the artist and OTP Copenhagen.

Astrid: As a painter you should find an object and use that object to be able to paint. Like Cezanne with his oranges - it’s not about the oranges it’s about painting. And that's how I see what you are doing. It's about these lists and about those words. At the same time they are just a vehicle for you to be able to be on the canvas. It's not necessarily about what is written there it's about the making.

Julie: I think working in this way also brings a place of rest, because you don’t need to come up with a new theme around whatever you are doing each time, because you know what you are doing. It’s like a form of anti-productivity that becomes productive. Now you have the frame and you can explore within that frame, because you know it will be a minijob or it will be a whiteboard painting, and that at least gives me some kind of calmness to be in the process.

Anouska: That is an antidote to what we talked about – the demand as an artist to always produce something new. That’s something brave as well as important.

Astrid: I don't feel it's brave, I think it’s just what artists do. When you say calmness we could also just say focus. I think there has been a misunderstanding from those surrounding artists and describing what artists are doing. Many are interested in defining the content of an artwork and using the content to prove a point.

Astrid Kajsa Nylander, baby blue minijob, 2025 [detail], oil on linen mounted on panel, 14.5 x 14.5 cm / 5.7 x 5.7 inches. courtesy of the artist and OTP Copenhagen.

Astrid Kajsa Nylander, baby blue minijob, 2025 [detail], oil on linen mounted on panel, 14.5 x 14.5 cm / 5.7 x 5.7 inches. courtesy of the artist and OTP Copenhagen.

Anouska: That’s something I can see and is a known critique from artists to art historians. It can be a beautiful thing when art conveys meaning to a wider perspective or current in society. It’s obviously out of the control of the artist, which I imagine is quite provocative sometimes.

Astrid: That's my concern – if we want to describe art, it’s disturbing when the description is not accurate.

Julie: That’s why it depends on from which position you are talking. Is it the artist, the art historian, the collector, the educator, the spectator?

Astrid: It’s an ongoing thing. Making art is like moulding or shaping something, things become clearer and vaguer along the way, and the same goes for how you want to describe what you are doing. It’s not constant – this comes back to the collapse. When something is existing, it is also falling apart.

Astrid Kajsa Nylander & Julie Koldby, minijobs & to-dos, installation view, 2025. Courtesy of the artists and OTP Copenhagen.

Astrid Kajsa Nylander & Julie Koldby, minijobs & to-dos, installation view, 2025. Courtesy of the artists and OTP Copenhagen.

Astrid Kajsa Nylander (b. 1989, Gothenburg; SE) lives and works between Stockholm and Gotland, Sweden. Nylander’s practice includes performance and installation in works that can be described as readings of painting in an expanded field. She studied Drawing and Painting for prof. Jutta Koether at Hochschule für bildende Künste Hamburg and graduated with an MFA in 2018. Works by the artist are held in the permanent collection of Moderna Museet, Stockholm, as well as other public collections.

Julie Koldby (b. 1993, Copenhagen; DK) lives and works in Copenhagen, Denmark. Working across media, Koldby’s practice consistently revolves around a performative model of thought, often emphasising ideas of energetic potential and the collapse of existing systems. Using fragile materials and emphasising impermanent states, Koldby presents us with sculptural scenarios. The artist holds an MA in Sculpture from the Royal College of Art, London, having completed undergraduate study at Malmö Art Academy, Malmö and Cooper Union School of Art, New York City.

Anouska Ingerdahl Kobus (b. 1993) is a curator based between Copenhagen and Paris. Ingerdahl Kobus holds a BA in Art History from the University of Copenhagen (2018), and a Master's degree in Contemporary Art Theory from Goldsmiths University of London (2021). She has worked as an exhibition coordinator and assistant curator at Kunsthal Charlottenborg. Since July 2023, Ingerdahl Kobus has worked as an independent curator and artistic advisor for artists Jeannette Ehlers and Alexander Tovborg. In parallel, she runs her own curatorial practice, through which she has curated several projects, including the group exhibition Fiction as Form at inter.pblc (2021).